Towards a Japanese “linguistics of speech”: semantic collocation in massive language corpora

Moved to http://kieranmaynard.com/bccwj

Translation of poetic drama “The Passerby” by Lu Xun 鲁迅《过客》英译

“The Passerby”

By Lu Xun (1925)

Translated from the original Chinese by Kieran Maynard (2013)

Time:

One day at dusk

Place:

Some place

Characters:

Elderly man: About 70 years old, white beard and hair, black long gown

Child: About ten years old, black (purple) hair, jet-black eyes, black and white chequered long blouse

Passerby: About 30 or 40 years old, exhausted and stubborn, gloomy expression, black beard, dishevelled hair, tattered black jacket and trousers, sockless feet and tattered shoes, carrying a sack by his armpit, leaning on a tall bamboo cane. (2)

East, are a few trees and rubble; west, is a desolate mass grave; in between is the trace of a sort of path. A small earthen hovel’s door is open toward this path; next to the door is an old tree stump.

(The girl is just about to help up the elderly man sitting on the stump.)

Elderly man: Child. I say, child! Why did you stop?

Child: (Looking to the east) Someone’s coming. Look!

Elderly man: No need to look. Help me inside. The sun is about to set.

Child: I… I’ll take a look.

Elderly man: Oh, this child! Every day you see this sky, this dirt, this wind; isn’t it good-looking enough? There’s nothing better looking than these. You just have to look at somebody. Things that appear when the sun sets won’t bring you anything good… Let’s go inside.

Child: But, they’re already here. Ah, it’s a beggar.

Elderly man: A beggar? Are you sure?

(The passerby staggers out from among the trees in the east, and after hesitating temporarily, walks slowly toward the elderly man.)

Passerby: Good evening, sir.

Elderly man: Ah, yes, much obliged. Good evening.

Passerby: Sir, I’m terribly rash, but could I have a drink of water? I’m awfully thirsty. Around here is there a pond, or a lake?

Elderly man: Oh, have a seat. (To the child) Child, bring water. Clean the cup.

(The girl goes silently into the hovel.)

Elderly man: My guest, please sit. What are you called?

Passerby: Called? I don’t know. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been on my own. I don’t know what I was originally called. On the road, sometimes people will call me by different names, all kinds of different ones, I can’t keep them straight, and to make matters worse, I’ve never been called the same thing twice.

Elderly man: Ah. Then, where are you from?

Passerby: (Somewhat hesitantly) I don’t know. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been walking like this.

Elderly man: I see. Then, can I ask where you are going?

Passerby: Naturally.: But, I don’t know. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been walking like this; I have to walk to someplace, and that place is straight ahead. I only remember walking many roads, and now I’ve come here. Next I will walk that way. (Points west,) Straight ahead!

(The girl carefully cradles a wooden cup and passes it to the passerby.)

Passerby: (Taking the cup) Thank you, young lady. (Downs the water in two gulps, returns the cup) Thank you, young lady. This is truly a rare kindness. I really don’t know how I should express my gratitude!

Elderly man: No need to be grateful; this will do you no good.

Passerby: Yes, this will do me no good. But now I’ve regained some strength. I must go on ahead. Sir, I suppose you have lived here a long while; do you know what it’s like up ahead?

Elderly man: Ahead? Ahead, are graves. (3)

Passerby: (Incredulously) Graves?

Child: No, no, no! Over there there are lots and lots of wild lillies, wild roses; I go and play over there a lot and go look at them!

Passerby: (Looking west, almost smiling) Not bad. Over there there are lots and lots of wild lillies, wild roses; I go and play over there a lot and go look at them. But, those are graves. (To the elderly man) Sir, what’s after the graveyard?

Elderly man: After it? That I don’t know. I’ve never been over there.

Passerby: You don’t know!?

Child: I don’t know, either.

Elderly man: I only know the south, the north, and the east, where you came from. That’s the place I’m familiar with, and probably actually the best place for you. Forgive me for intruding, but from what I can see, you’re already exhausted; you ought to just go back, because I’m not sure you can make it to the end if you go ahead.

Passerby: Not sure I can make it to the end?……(Pensive, suddenly stands) That won’t do! I have to go. Going back there, there’s not one place without a title, not one place without a landlord, not one place without explusion and jail, not one place without smiling faces, not one place without tears outside the eye socket ??? I hate them; I won’t turn back!

Elderly man: It’s not like that. You will also find tears from the bottom of the heart, and grief for you.

Passerby: No. I don’t want to see their heartfelt tears; I don’t want their grief for me!

Elderly man: Then, you, (shakes his head) you have to go.

Passerby: Yes, I have to go. Furthermore, there’s still a voice ahead of me urging me, calling me, making me short of breath. Unfortunately my feet have already walked to pieces, they have many wounds, they’ve shed much blood. (Lifts a foot to show the elderly man) Therefore, I don’t have enough blood; I need to drink some blood. but where is there blood? But I won’t drink just anyone’s blood. I can only drink some water to replenish my blood. As long as there is water on the road, I actually don’t feel any insufficiency. Only my strength is too weak; perhaps there is too much water in my blood? Today I didn’t even find a pond; perhaps because I didn’t walk enough?

Elderly man: Not necessarily. The sun has set. I think you ought to rest a while, like me.

Passerby: But, the voice ahead tells me to go.

Elderly man: I know.

Passerby: You know? You know that voice?

Elderly man: Yes. It seems in the past it has called me.

Passerby: And that’s the voice that’s now calling me?

Elderly man: That I don’t know. It only called a few times, I ignored it; it never called again. I don’t remember clearly.

Passerby: Ah, ignore it… (Pensive, suddenly surprised, listens) No! I still have to go. I can’t catch my break. Unfortunately my feet have already walked to pieces. (Prepares to walk)

Child: This is for you! (Hands him a piece of cloth) Wrap up your wounds.

Passerby: Thank you. (Takes it) Young lady. This is truly… This is truly a rare kindness. (Sits down, about to wrap the cloth around his ankle) But, no! (Stands forcefully) Young lady, you take it back, I won’t use it. Furthermore this is too much kindness, I can’t be grateful enough.

Elderly man: You don’t need to be grateful; this won’t do you any good.

Passerby: Yes, this won’t do me any good. But for me, this charity is the greatest of things. See, my whole body is like this.

Elderly man: Just don’t think of it that way.

Passerby: Indeed. But I can’t. I’m afraid I will be like this: if I happen to receive someone’s charity, I will just be like a vulture who sees a corpse, lurking on all sides, praying for her demise, to see it with my own eyes; or cursing the demise of everything outside of her, even myself, because I too should be cursed. (4) But I don’t have this kind of power; even if I had the power, I wouldn’t want her to have that kind of encounter, because they most likely don’t want to have that kind of encounter. I think, this is most proper. (To the girl)

Young lady, this cloth is too good, but a little too small, you take it back.

Child: (Frightened, retreats) I don’t want it! You take it!

Passerby: (Almost smiling) Oh… because I’ve held it?

Child: (Nods, points at the sack) You put it in there, go play.

Passerby: (Dejectedly retreats) But with this on my back, how can I walk?

Elderly man: You can’t catch your breath, or carry it. : Rest a while; it’s nothing.

Passerby: Right, rest… (Thinks silently, but suddenly surprised, listens) No, I can’t! I still have to go.

Elderly man: You’re never willing to rest?

Passerby: I’m willing to rest.

Elderly man: Then, why don’t you rest a while?

Passerby: But, I cant…

Elderly man: You always think you had better go?

Passerby: Yes. I had better go.

Elderly man: Then, I suppose you ought to go.

Passerby: (Straightens his back) All right, farewell. I’m very grateful to you. (To the girl) Young lady, I’ll give you this, please take it back.

(The girl is frightened, pulls back her hands, ready to hide inside the hovel)

Elderly man: Why don’t you take it? If it’s too heavy, you can throw it away somewhere in the graveyard.

Child: (Comes forward) Ah! No you can’t!

Passerby: Ah, no you can’t.

Elderly man: Then, you can hang it on the wild lillies or wild roses.

Child: (Claps) Haha! Ok!

Passerby: Oh…

(Very briefly, pensive)

Elderly man: Then, goodbye. I wish you well. (Stands; faces the girl) Child, help me inside. Look, the sun has already set. (Turns toward the door)

Passerby: Thank you. I wish you well. (Hesitates, pensive, suddenly surprised) But I can’t! I have to go. I still had better go… (Immediately looks up, hurriedly sets off west)

(The girl helps the old man into the hovel and closes the door. The passerby staggers into the wilderness, night following behind him.)

April 2nd, 1925

(Trans. Jan. 8, 2013 in Shanghai)

Notes

(1) First published April 9, 1925 in the 17th volume of the weekly “Yǔsī” (pronounced “Yoo-ss”, meaning “Word Threads”)

(2) 等身 as long as a person is tall

(3) “Graves”; c.f. the author in “Written After ‘Graves'” once wrote, “I am only very certain of an end point; that is: a grave. This everyone knows, and don’t need it pointed out. The problem is only the way from here to there. Of course there isn’t just one path, I just don’t know which path is right, despite that up until now at times I have searched for it.” (See 《写在〈坟〉后面》)

(4) Not long after writing this piece, Lu Xun in a letter to Xu Guangping wrote, “While those who are connected to me are alive, I actually can’t be at ease; when they die, I can rest easy; this is also expressed in ‘The Passerby.'” (See《两地书 • 二四》)

Source material: 《野草》鲁迅,大学生必读,北京:人民大学出版社,2002年

Translation of “Tree on the Bluff” by Zeng Zhuo 曾卓“悬崖边的树”英译

“Tree on a Bluff” by Zēng Zhuō (1922-2002)

Rhyming loose translation

I know not what wind brought this tree

to this flatland’s edge on the bluff;

She listens for the far forest’s clamor

And signing of streams in the rough

It stands by itself all alone

Looking obstinate, and lonely;

Its body a mass of tangles,

Wind-twisted, bony.

It keeps the shape of the wind,

seems about to cave in,

and yet soon to spread wings and take flight.

2012.11.18 evening

Shanghai

Literal translation

I do not know what strange wind

blew a tree over there——

the end of a plain

on a crag overlooking the valley

It listens closely to the clamor of a far forest

and the singing of streams in the valley

It stands there alone

looking obstinate, and forlorn

Its crooked body

retains the shape of the wind

It looks ready to fall off into the valley

and yet about to spread wings and take flight……

1970

Original poem

悬崖边的树

曾卓

不知道是什么奇异的风

将一棵树吹到那边—–

平原的尽头

临近深谷的悬崖上

它倾听远处森林的喧哗

和深谷中小溪的歌唱

它孤独的站在那里

显得寂寞而又倔强

它的弯曲的身体

留下了风的形状

它似乎即将跌进深谷里

却又像要展翅飞翔……

一九七〇年

Translation of “Wanderer” by Mu Dan 穆旦“流浪人”英译

“Wanderer”

(“Liúlàng rén”)

Mù Dàn (1918-1977)

Trans. K. Maynard

hunger——

my good friend

it keeps pestering me

on this wandering road

softly,

the wanderer’s two heavy legs

step, after step, after step……

what place at earth’s end?

no destination. only

two legs moving

step, after step…… wanderer

as if eyes bloomed a flower

flew past a million stars, crow-like.

muddled head, bitter heart;

fiery-hot body, melted——

like cotton, heaped into a ball

but still carrying soft legs

step, after step, after step……

(1933) 4.15 evening

流浪人

穆旦

饿——

我底好友,

它老是缠着我

在这流浪的街头。

软软地,

是流浪人底两只沉重的腿,

一步,一步,一步……

天涯的什么地方?

没有目的。可老是

疲倦的两只脚运动着,

一步,一步……流浪人。

仿佛眼睛开了花

飞过了千万颗星点,像乌鸦。

昏沉着的头,苦的心;

火热般的身子,熔化了——

棉花似地堆成一团

可仍是带着软的腿

一步,一步,一步……

(1933年)4月15日晚

[Kansai Travelog] Walking the Philosophers’ Way in Kyoto

Dear Readers:

Today I met a video game character designer named Yamazaki and his wife. We met on CouchSurfing, and agreed to meet in Ueda. While wandering around before the meeting, I came upon a shrine called Tsunashiki Tenmangu Otabisho 綱敷天満宮御旅所, or Tsunashiki Tenjinja. (It has a website here: http://www.tunashiki.com .) Sitting between buildings on a street next to Kappa Yokocho, Tsunashiki Shrine caught my attention because of its steep steps, and the “Otabisho” part of its name. A “tabi” is a journey in Japanese, and sure enough Tsunashiki is a shrine for ryoko anzen, or safe travels. I offered some yen and bought an omikuji. It was lucky, but recommended I hold back and not try to do too much. As for direction, anywhere south was good. As for travel, it suggested I quit. I tied up the omikuji to ward off the bad luck and bought an o-mamori charm for safe travels. Of course, I can’t quit, so I have the charm. The lesson on the back of the omikuji read something like, “The high peaks tower in the blue sky, but if you climb, there is a way up.”

I ate curry in Kappa Yokocho, got lost around Umeda walking up and down platforms through crowds and department stores, and drank some bottled ginger jujube tea. I met Yamazaki at Yodobashi camera and we tried two cafes before we found one with empty seats. He kindly treated me to coffee and we talked about Kyoto, where he attended university, learning languages, traveling in Rome and Europe, and his dream to hold an international art exhibition in London. Also, he designed two characters in the video game Street Fighter 4.

Art in the Isetan department store

We went to Isetan department store to see an art exhibition called Girlie Show. The theme was “girls,” and women artists from around Japan depicted girls in various styles on small canvasses. Prints of artworks and goods like iPhone cases were on sale, and one or two of the artists were present. We then went upstairs and saw the “Art Liberation Space” or something like that, where various works were exhibited, like ceramic cups crawling with metal insects. In the back was an exhibiton called “The Beauty Adventurers” (美の冒険者たち) if I remember correctly. The artists were students, graduates and faculty at an art college in Osaka. I enjoyed the various styles and materials and the high level of artistry in the works, and happily spent an hour with Yamazaki gazing at paintings.

Tsukemen noodles in Ueda

We met Yamazaki’s wife at Loft variety store and went to a nearby shop for tsukemen (dipped noodles), which were delicious. The roast pork on top was expecially good. The Yamazakis gave me lots of advice about Kyoto, and we talked about what we had done that day. I received advice from a pair who had studied art in Kyoto. What could be better! When I mentioned that I saw the guardian statues at Todaiji Temple in Nara, Yamazaki told me those are by a famous artist of the Edo period. I took notes on place names in Kyoto, and they kindly saw me back to the subway. The next time I see them, perhaps their first child will be born!

Kieran

Dear Readers:

Yesterday I bought a day pass and took the train from Osaka to Nara. From August 4-14, the Tokae (燈花会), or “Flower Lantern Festival” is being held in Nara Park. I rented a bike, cycled around the ruins of the ancient capital, and spent the evening watching the lanterns light.

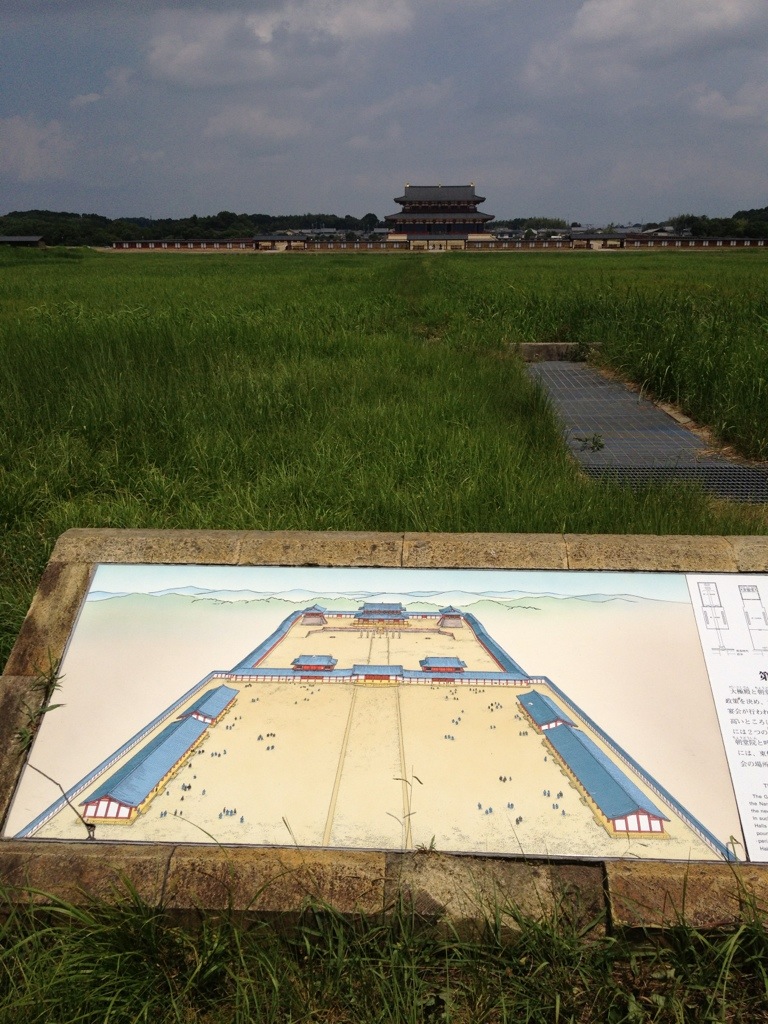

Cycling the Imperial Capitol Ruins

I wanted to go to Nara for two reasons. Nara was for 75 years the capital of the Yamato empire after the capital was moved from Fujiwara around the year 710, and is full of old temples. I got off the train at Yamato-Saidaiji and rented a bike. I cycled through the crowded roads across the river to the grassy plain that is the site of the former imperial residence. The site is roughly divided into an eastern and western half. During the first half of the Nara Period (as the era in which Nara was the capital is called), on the west side stood the imperial complex, where the courtiers would gather for ceremonies while the emperor sat on the throne. During the second half of the period, a second complex was build on the eastern side, and the old buildings were used for banquets. At the end of the period or sometime thereafter, all the buildings were demolished, and the metal roof ornaments probably melted down for reuse. All that remains today are some raised platforms, and marks in the soil where buildings once stood.

Today, two buildings stand at the north and south ends of the western complex: the Suzaku Gate (朱雀門) and Daigoku Hall (大極殿). Both were reconstructed after extensive archaeological studies. The original appearance of the buildings are unknown, so the designs of the reconstructions are based on drawings of period buildings and the designs of still-standing medieval structures, like the East Tower in Yakushiji temple. I entered the complex through the bright red Suzaku Gate. The Suzaku is a legendary Chinese bird that represents the south. In Chinese mythology, the cardinal directions are represented by animals. The Suzaku represents the south, and the north, east, and west are represented by the Genbu turtle, the Byakko white tiger, and the Seiryu green dragon, respectively. (I have given the Japanese pronunciations.) From the Suzaku Gate the Daigoku Hall stood tall in the field in the far distance. A commuter train cuts right across the site today. I imagined I was an emissary arriving from Tang China or some other faraway place as I stood in the Suzaku Gate. I biked across the train tracks to the courtyard before the Daigoku Hall. The sky was clear and blue and puffy clouds were scattered above. Certainly, the imperial courtiers 1,300 years ago must have stood stiff in the cold on New Year’s morning and looked up at the same sky.

I wandered around the station, mailed my disc of photos back to America, and bought a handmade bento lunch. In the bento shop, I expected stacks of made-yesterday boxes, but the only thing in the shop was a cooler of drinks and a counter. When I ordered a maku-no-uchi bento, I waited about ten minutes for the fried things to fry and whatnot. I ate my bento on the steps of the eastern compound. Behind me, workers cut the head-high summer grass. Clouds lazed in the blue sky, I chewed on a fish stick, and cicadas buzzed in the trees. In the main hall was a message left by the emperor on his visit to the opening ceremony. He wrote, “Research upon research, and restoration. Daigoku-den now stands before our eyes.” (御製=研究を重ねかさねて復元せし、大極殿いま目の前に立つ)

South of the capitol: the Nishi-no-kyo area and Yakushiji Temple

I rode along the river to the Nishi-no-kyo area, which means “the west [part of] the capital.” Indeed, it was the western part of the city south of the Suzaku Gate, and two famous temples still stand there. Yakushiji Temple, or the temple of the Buddha of Medicine, was commissioned by the emperor about 1,400 years ago to help his wife recover from illness. She did recover, and took the throne herself when the emperor died before the temple’s completion. The buildings have burned and been rebuilt several times, but many date back to the 16th and 17th centuries. I most wanted to see the East Tower, which is said to have stood for over 1,300 years, which I assume would make it one of the oldest wooden buildings on earth. It is the only building in Japan that survives from that period. Alas, the entire structure was covered in opaque scaffolding. It has been 100 years since the structure was last renovated, so it is being dismantled and reassembled.

On the back wall of the main hall were plaques with the story of the Buddha. When he died, the Buddha’s last words were something like, “Remember what I have taught you, and believe in yourself.” Inside the hall were three statues from the Nara period, of Yakushi flanked by Nikko and Gekko, the Bodhisattvas of sun and moonlight. Exposure to fire turned the 1,300 year old statues black.

Kasuka Shrine, Nara deer, and the Flower Lantern Festival

I rode four kilometers from Saidai Temple to Nara proper and returned the bike. I got it in my head to visit Horyuji Temple and took the train south, but it was too far away, so I didn’t make it. On the way back from Tsutsui to Nara, I met four middle school guys on the train. They had dyed hair and earrings and poked fun at each other while we talked, like “He’s from North Korea!” and “He pees all the time!” I said I wondered what it must be like to live in a legendary place like Nara, and they said, “We’re legendary children!”

I walked the omote-sando path into Kasuka Shrine inside Nara Park. When the Flower Lantern Festival ends, a Ten Thousand Lantern Festival will be held in Kasuka Shrine 春日大社. Along the path were hundreds or thousands of stone lanterns densely placed. I happened upon a meeting hall at the edge of the park where the mountains begin and walked through the garden behind. I emerged in a field of little lanterns, plastic cups of different colors arranged in different shapes, like stars and hearts and flowers. Groups of volunteers, from little kids to elderly people, were putting water in the cups, and then candles. In addition to lanterns and people, the field was full of deer. Little deer followed the big deer, and all the deer moved slowly in a big pack near the picnic tables beneath small trees. I helped a little boy shoo the deer away when they came to drink the water from the cups. A sign said, “One guest, one lantern,” and they were being sold were 500 yen (~$6). The western sky was gold in sunset, and as the sun disappeared behind Todaiji Temple’s main hall and the treetops below, the eastern clouds turned pink over the mountains.

The Flower Lanterns and temples at night

As the sun set, the volunteers lit the lanterns at about 7 PM. From then, the festival began in earnest. People began streaming into the park, buying lanterns to add to the designs and strolling down the shop walks in yukata and sandals. I walked among the flickering shapes, down a street of food stalls, and down the dark stone path to the vast gate at Todaiji Temple. Giant statues some twenty feet tall flanked the gate, which was a peeled-paint color of rusty brown, and looked very old. Todaiji was closed, but I peered through the gate at the massive wood hall, probably the biggest wooden building I have ever seen. I ate Hiroshima-style okonomiyaki at a stall and walked down rows of candles out of the park. I happened upon Kofukuji Temple and the Five Story Pagoda. The old pagoda was dramatically lit, and a hall was open for night prayers. A group was gathered near the foot of the tower around lanterns shaped on the ground. The shape was the kanji “再”, pronounced “sai” in Japanese, as in saikai 再会 ‘reunion’, saiken 再建 ‘rebuilding’, and saisei 再生 ‘rebirth.’

The commercial streets and lesson of Nara

The main hall of Kofukuji was also covered in scaffolding for rebuilding. I made an offering at the octagonal hall and descended stone stairs into a brightly lit shopping street. I passed shops and crowds and ate a ball of green mochi filled with red bean and powdered with kinako soy powder. A trail of lanterns snaked up a stairway to a little Shinto shrine.

Walking among the crowds at Nara station, I felt silly for having rushed to Horyuji Temple. I think I had expected Nara to be a tourist trap, full of tourists hemming and hawing over big Buddhas and big halls like in Kamakura. In fact, Nara is a thriving provincial capital with a living religious tradition. The temples are far apart and far too many to see every one. Many things are unpretentiously old. To make a French analogy, Nara might be Lyon to Osaka’s Paris. I had heard the oldest such and such and the biggest such and such building were in Nara, and those extremes loomed too large in my mind. What of history I was able to feel in the ruins and what of local belief I was able to understand in the sacred places was good enough. It’s not to say I didn’t miss things I’d have enjoyed seeing, but that I didn’t make it to some place or other makes no difference at all.

Kieran

Dear Readers:

During a day wandering among temples, I realized that I came to Osaka with a false impression. In the early 1970s, the writer Sawaki Kotaro traveled by train and bus from Bangkok to Singapore. In every city, he felt something was missing. The excitement he’d found in Hong Kong wasn’t to be found in Thailand or Malaysia. On the eve of leaving Singapore, he realized, Singapore isn’t Hong Kong. It seemed too silly to say out loud, but he’d been looking for a copy of Hong Kong everywhere he went. Certainly, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok must have their individual charms.

I assumed Osaka was a loud and crowded place, on flat ground, without much that would carry me away. I was wrong. Shin-sekai, around the now 100-year old Tsutenkaku tower is indeed a place of boisterous bars, and not a boring place to visit. Shitennoji is a world apart.

Shitennoji District (四天王寺)

I happened to be staying next to Tennoji station so I took the subway past it on a whim to make my 200 yen go farther. I alighted at Shitennoji-mae Yuhigaoka Station, which means “In front of Shitennoji (and) Sunset Hill.” It turns out, the Shitennoji area is full of temples, leading south to Shitennoji Temple itself. I learned a lot about Japanese Buddhism by reading the signs. I turned a prayer wheel carved with scripture in Chinese. I met a group of high school students near Yuhigaoka Academy. On a stele was carved in Chinese the exploits of the writer’s father, Date Munehiro 伊達宗広, according to the nearby explanatory board. He loved the songs of a songwriter Fujiwara Ietaka 藤原家隆 who lived many generations before him, so he made his home in the same place, and named it “Sunset Hill” after one of Fujiwara’s poems. They are both buried nearby. While reading the sign, a man working on his 600cc shiny black Honda came over, and we talked about my travels, my brother Pace’s travels in America, and the history of Osaka. His name was Kishino, and he told me to go on to Shitennoji, past the tower we could see over a parking lot.

The tower turned out to be a 400-year-old national treasure, a pagoda to store the treasures in Aisen-san 愛染さん temple. It was the model for a temple once erected at the Japanese pavilion at the World’s Fair in San Francisco. Aisen-san itself was bright red.

The Seven Slopes (七坂)

There are seven slopes among the temples. I came up Kuchinawa Slope, which a writer once climbed and thought, “I won’t be climbing this slope for a while, I suppose,” whereupon he came to feel that the sweetness of youth was over, and a new reality had come to face him. I stopped for ramen, and ate “Osaka Black” salt-broth ramen with thick noodles (you could choose thick or thin). The dark broth had an edged flavor. I walked down Aisen Slope to a temple that holds Kinryu and Ginryu Ido, or the “Golden and Silver Dragon Wells.” Alas, they dried up when the subway was built, and Ginryu is buried in concrete. However, a woman from the temple named Asano showed me to Kinryu Well, in which we could see our reflections! The water has come back, little by little, though we can’t yet drink it again to get the sweet taste that was once favored in the tea ceremony.

Kiyomizu Temple and the deadly fault line

I climbed Kiyomizu Slope to Kiyomizu Temple, which shares a name with an illustrious temple in Kyoto. From the hill at the Kiyomizu graveyard (which was packed with a tour group for a few minutes), a vast stretch of Osaka can be seen, including a tower still unfinished at Tennoji Station. I went down to see the waterfall at Kiyomizu, and a man was chanting sutras before the statues behind the water. As I left, a man named Satoshi spoke to me in perfect English. In what was quite likely the first all-English conversation I’ve had with a Japanese person this trip, he told me he worked for the IT department at Stanford and lived in California. He was surprised I came to Kiyomizu, which he visits often, because he seldom sees tourists there. He asked had I noticed the slopes and varied elevation in the area? I had, but he informed me that the slopes are due to a dangerous fault that runs under the area. The line of temples and shrines are built on the fault to prevent disaster with their power.

Isshin Temple and modern decor

I went through a shrine with cats and a man behind the counter who explained the Warring States history of the area. Across the street was a temple far busier than the sleepy ones I had visited. Isshin Temple (一心寺) lost its gate, so a very modern gate was built to replace what had been called the “Black Gate” or Osaka. Indeed, the gate is made of a honeycomb of black metal, and two utterly fearsome guardians wave green fists over heavenly ladies embossed in dark steel. The temple grounds were packed. I prayed in the main hall and offered incense, and a very old couple encouraged me to go to Sapporo.

Shitennoji and the story of the Buddha

Up the street, I walked down the arcade to Shitennoji, the biggest and busiest of all. The red five-story pagoda indeed towered over the hall at Aisen, and every building in Shitennoji was painted red and white. Inside the main hall, wall paintings told the story of the Buddha, from his miraculous birth under the right armpit of Maya, to his death and entrance into nirvana at the age of 81. Most impressive was the scene of the Buddha returning, enlightened, to speak at the Deer Garden. He wore simple clothes and his face was calm and pure, and a light emanated from his brow. In the forest, those who had known him before fell to the ground and reached out their hands in awe to see Gautama so transformed. (According to the explanations written below.) The Buddha had also been attacked by a host of demons, but their arrows turned to floating lotus blossoms and the beautiful women sent to seduce him suddenly grew old. The story was mostly new to me, so I am keen to read more. Another hall told the story of Xuanzang 玄奘, who spent 17 years on a journey from Chang’an to India and back. Upon his return, he and a team of scholars translated hundreds of scriptures, which were stored in the Great Goose Pagoda that I visited last year in Xi’an.

If only I could tell you everything I learned today. I’d never get any sleep. I walked among the bars around Tsutenkaku tower and spent a mostly fruitless and expensive hour in a net cafe trying to copy photos.

Osaka is alive!

Best,

Kieran

Tokyo and the Sky Tree

July 18, 2012

Back in Tokyo

Bakuro-cho, Asakusabashi, Sumidagawa, Sumida-ku, Midori-cho, Kamezawa-cho, Edo-Tokyo Museum, Tokyo Sky Tree

Seattle to Tokyo

Flew via Seattle to Tokyo, and slept an hour on a bench in the Sea-Tac airport. Started and almost finished Dazai Osamu’s novel Arrived late around 6:30PM local time. Rode the train in from Narita. The sky was fearsome bright over Narita town in the evening. Trucks rolled over a bridge and a red tower peaked over green trees before an orange sky.

Tsukemen in Asakusabashi

I slept at the Khaosan Tokyo Ninja hostel in Asakusabashi and met a guy from the Phillipines while drinking tea in the common room downstairs. I walked across the Asakusa bridge looking for the ramen place the girl at the desk recommended. I happened upon it under the rattling train and ordered tsukemen from the ticket machine ($10). I sat between two guys on lunch break and dipped the noodles a mouthful at a time. When I had eaten them all, and the pork that was roasted with a blow torch behind the counter, I filled the soup with hot water and drank some.

Midori-cho

I walked about Bakuro-cho among little cafes and restaurants, and across the Sumida River. Next to the river was a relief of nine faces representing artists inspired by it. I passed under an overpass toward Ryogoku, and on a map was a mark for the former residence of Kobayashi Issa (a haiku poet) in Midori-cho. I didn’t find Issa’s former home, but two surveyors in blue peered into a gadget on a tripod while workers with a crane lifted a huge pipe off a barge. A highway overpass ran the whole length of the river. A little boat came in among the barges. The crane had “I will not cause an accident” (私は事故を起こしません) written on its arm. The workers guided the pipe with ropes to the artificial embankment they were building, set it down, and started cutting it with a saw. Another worker stood welding a pipe’s mouth, and the smoke plumed up toward the highway.

Hokusai-dori

I walked back through Midori-cho among nondescript buildings, and then Kamezawa. Along Hokusai-dori were prints of Katsushika Hokusai’s works stuck to the lampposts, such as some of the “36 Views of Mount Fuji.” Apparently, Hokusai was born in Kamezawa. I passed kids on the street and a playground covered with kids who looked like they’d just got out of class. Across the street loomed the gray battleship-like Edo-Tokyo Museum. I walked up the wide and empty stairs and under the elephantine metal exhibition hall. The wide and flat platform looked out over Tokyo.

Edo-Tokyo Museum

I bought a ticket and took the escalator up a bright red animal organ-like tube into the belly of the elephant and walked through the museum. Inside was a reproduction of the wooden Nihonbashi from 19th century, among other things. I saw lots of exhibits about Edo, from the time that the shogun turned it from a fishing village into a military headquarters, to the time it became Tokyo after the Meiji Restoration. I learned that people who were granted an audience with the shogun were called hatamoto (旗本), or “bannermen” and were provided individual residences. Other household workers in the shogunate, called gokenin (御家人) lived in communal quarters. Around 1720, there were about 5,000 bannermen, and about 17,000 household workers. Sometimes land was provided that could be used for income, but usually salaries were paid a few times a year, in rice from the shogun’s granary.

In 1854, Commodore Perry forced the shogunate into an unequal treaty with the US, and the establishment of trade relations ended the closed door policy. In the museum were drawings from news clippings depicting the fearsome American steamships. After the Meiji Restoration, there was debate about whether to establish the national capital at Kyoto, Osaka, or Edo. A “two capital” policy was favored for a while, and thus Edo’s name was changed to Tokyo, the “Eastern Capital.”

Kaya-dera

I took the train to Kuramae. Leaving the station to change trains, I passed by Kaya-dera (榧寺), a small Pure Land temple with two concrete pillars shielding a little garden, and a squat modern-make building with attached cemetery. Inside were sumptuous golden decorations at the altar. A sign showed that Hokusai once painted Kaya-dera in a painting called something like “The High Lantern at Kaya Temple” (榧寺の高燈籠) which shows some people in a boat behind the temple.

Tokyo Sky Tree

I went on to Oshiage to see the Sky Tree. Newly opened, the Sky Tree is an impressive tower that changes from a trangle shape at the bottom to a circle at the top. It looks like an old Soviet TV tower in a way, but also a bit organic in its bend. Inside the ticketing area were 12 objets d’art representing the tower, each made of a different Japanese craft, and paired with a Japanese virtue. The crafts are listed here: http://blogs.futaba-en.jp/2012/06/super-craft-tree.html (Japanese).

I walked through the “Japanese Experience Zone” (expensive mall) and took the elevator up to the Dome Garden. There, a silver dome greets the Sky Tree on one side, and the partner building on the other, whose glass reflects the Tokyo tree. Kids played on the grass by the dome, and on the other side wordless music played while people slept or lounged on wooden benches. Green plants lined the black fence, and the sky was blue with white clouds behind the Tree, and the orange sun peeked through.

Have you seen the Sky Tree? What do you think of it?

-Kieran

“Ramen” original speech ラーメン ― 弁論大会優勝作品

English translation below. I produced this original speech for a contest in 2012 with the help of my advisor Dr Masaki Mori. The historical speculation feels highly amateurish to me now, but it was with this speech that I won a solo trip to Japan that enabled me to produce the travelogues I’ve also included on my site.

弁論大会

2012年3月20日

ラーメン

キーラン・メイナード

アメリカで嗜好されている日本食品の中で、特に親しみを持たれているのはラーメンです。なぜなら、ラーメンはカップヌードルとして渡来して久しいからです。ですが、私が日本でびっくりした事は、ラーメンがカップヌードルだけでなく場所や店によって色んな形や味をしているという事でした。私の住んでいた町は「博多ラーメン」で有名な福岡でした。博多ラーメンの特徴はスープが豚骨から作られている事です。

「ラーメン」という名前は中国語で、手で引っ張って作られた麺という意味で、中国の最も一般的なラーメンは「蘭州ラーメン」という牛肉ラーメンです。蘭州ラーメンを売っている店の多くはイスラム教徒の経営で、豚肉は使いません。それに、中国ではラーメン屋で麺を手で打つ作業が見られ、値段は日本に比べて10分の一くらいです。

では、ラーメンはどうやって日本へ渡り、変化したのでしょうか?伝説によると、麺という食品は中国から絹の道を辿り、地方によって様々な形になりました。イタリアではパスタになったし、日本の場合はうどんでした。約1300年前、中国の唐代の頃、中国大陸と九州間の交流が盛んになって中国人が九州の北部へ来ました。福岡は、うどんを初めとして、日本での中華文化の発祥の地です。ラーメンが日本で普及した沿革は二十世紀の始め頃で、「中華そば」と呼ばれ、中華街で売れていてラーメン屋台がだんだんラーメン専門店に変わったのでした。けれども、博多ラーメンが有名になったのは、さらに後の「ご当地ラーメン」の流行に由来します。70年代の頃、ラーメンが場所の特徴を現す特産として日本文化の中に特別な地位を占めるようになりました。

「場所らしさ」、或いは場所の特徴は重要です。人々は場所の特徴を誇るために(そして観光客を勧誘するためにも)色んな事物を作って強調し、「ここは桜が全国で一番綺麗」とか、「ここはうどんが一番おいしい」とかと主張します。私の考えでは、その場所らしさを強調する傾向は戦後始まり、日本の都会が殆ど同じに見えるようになったことから発生しました。住民が他の土地へ移動したり、建物が壊されて鉄筋コンクリートに建て直されたりした結果、土地の特徴を現す物が少なくなったので、60年代の後半以降、ラーメンは似たりよったりになった町々に特徴をつけるものの一つとして用いられるようになったのです。

最初に述べたように、アメリカでは一般的にラーメンと言うと安く買えるカップヌードルのことですが、それでもニューヨークには博多ラーメンの一風堂があり、ジョージア州には美味堂(うまいどう)があります。将来和風ラーメンはもっと広く知られるようになるでしょう。

Benron Taikai

3.24.2012

Ramen

Kieran Maynard

Among the Japanese foods enjoyed in America, ramen is especially familiar to Americans. Ramen has long been known in America as “cup noodles.” However, I was surprised to find that, in Japan, “ramen” is not only cup noodles, but takes many forms and flavors in different places and restaurants. I lived in Fukuoka, famous for “Hakata ramen.” Hakata ramen’s special characteristic is that the soup base is made with pork bones.

The name ramen is Chinese (lāmiàn), and refers to noodles that have been stretched and shaped by hand. The most general Chinese ramen is a beef ramen called Lánzhōu lāmiàn. Most restaurants that sell Lánzhōu lāmiàn are operated by Muslims and do not use pork. Also, at ramen restaurants in China the process of making noodles by hand can be seen, and the price is around 10% of ramen in Japan.

So, how did ramen cross over to Japan, and how did it transform? According to legend, wheat noodles came from China, traveled the Silk Road, and took various forms in different places. In Italy, they became pasta, and in Japan became udon. About 1,300 years ago, during China’s Tang dynasty, exchange developed between the Chinese mainland and the island of Kyushu, and Chinese people came to the northern part of the island. Starting with udon, Fukuoka is the birthplace of Chinese culture in Japan. Ramen, called “Chinese soba” and sold in Chinatowns, became commonplace in Japan during the early 20th century as ramen food stands became ramen specialty restaurants. However, Hakata ramen became famous because of the later “local ramen” craze. In the 1970s, ramen came to occupy a special place in Japanese culture as a product that expresses the characteristic of a locality.

“Sense of place,” or the character of a place, is very important. To extoll the characteristics of a place (and to attract tourists), people make up and emphasize various things, claiming, “Here the cherry blossoms are the most beautiful in the nation,” or, “Here udon is the most delicious.” The way I see it, this tendency to emphasize sense of place began after World War II, due to the fact that Japan’s cities came to look mostly the same. As residents moved to other places and buildings were destroyed and rebuilt in ferroconcrete, the things that express the characteristics of places disappeared, and thus from the latter half of the 1960s, ramen came to be used as something to give character to the towns that had become indistinguishable.

As I said in the beginning, when we say ramen in America, we usually mean the cheaply available cup noodles, but even so, there is the Hakata ramen restaurant Ippūdō in New York and Umaidō here in Georgia. In the future, perhaps Japanese ramen will become more widely known!